Guidelines for submitting articles to Santa Rosalia Today

Hello, and thank you for choosing Santa Rosalia.Today to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

Santa Rosalia Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on Santa Rosalia Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@spaintodayonline.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb

The sinking of the Castillo de Olite

The worst naval catastrophe of the Spanish Civil War took place in the harbour of Cartagena

The story of the Castillo de Olite, sunk in 1939 in Cartagena

It is generally agreed by historians that the final phase of the Civil War in Spain lasted from approximately December 1938 to April 1939. At this time Franco ordered his forces to invade Catalunya; it seemed that the central eastern part of Spain would fall in a matter of just days, and only the central southern part of the country remained in the hands of the Republicans, who by this stage were practically unable, and in many cases unwilling, to fight on in the defence of a losing cause.

It is generally agreed by historians that the final phase of the Civil War in Spain lasted from approximately December 1938 to April 1939. At this time Franco ordered his forces to invade Catalunya; it seemed that the central eastern part of Spain would fall in a matter of just days, and only the central southern part of the country remained in the hands of the Republicans, who by this stage were practically unable, and in many cases unwilling, to fight on in the defence of a losing cause.

Cartagena was still in the hands of the Republicans, but only just.

The Republic was on its knees and stricken by internal conflicts, including an uprising at the naval base of Cartagena, and its complete disappearance could be delayed only by a last desperate show of resistance which might prolong the conflict long enough for it to become part of the wider international struggle which was about to engulf the whole of Europe, the Second World War.

Franco, fully aware of this, and also having received information concerning the apparent lack of unity in the defences in Cartagena, ordered that troops be sent to the city, where the Republican fleet was still at anchor. He knew that this was the Republicans' last throw of the dice, and that if Cartagena were to fall then the war would be almost over.

The plan to disembark troops in Cartagena was on a scale hitherto unknown in the Civil War: thirty transporters and warships were hastily dispatched from Castellón and Málaga, carrying more than 20,000 men, with only 48 hours preparation. Theirs was a mission fraught with risk: the ships were crammed with troops, and had to sail more than 150 miles along a coastline still controlled by the enemy, without any protection. Each vessel was left to fend for itself, and none of those aboard really knew what reception awaited them in the port of Cartagena.

Safety was sacrificed in the name of speed, and the result was yet another tragedy of war. The ships boarded by Franco's troops in Castellón set sail one by one: as soon as one was prepared to sail it headed for Cartagena, without waiting for the rest. The first set off at midnight on the night of 5th/6th March, but the "Castillo de Olite", one of the slowest vessels involved, with a maximum speed of only ten knots, did not leave Castellón until after ten o'clock the following morning. According to some reports, the ship's radio was not functioning properly, and it sailed alone and uninformed to its destination.

The fleet arrived at its target on the misty morning of 7th March 1939, but Cartagena was successful in resisting the attack, and the attacking fleet dispersed, all the vessels returning to the ports from which they had come.

The fleet arrived at its target on the misty morning of 7th March 1939, but Cartagena was successful in resisting the attack, and the attacking fleet dispersed, all the vessels returning to the ports from which they had come.

All, that is, except one. At about 11 o'clock in the morning, the "Castillo de Olite" reached the area of Escombreras at the entrance to the harbor, but a warning shot from the "La Curra" battery was ample evidence that the city was still controlled by the enemy.

The ship prepared to turn around and head back out to sea, but soon afterwards it was hit on the bridge by a shell fired from the "La Parajola" battery, and quickly sank after an explosion in the heart of the vessel.

Of the 2,112 men on board, 1,476 lost their lives. In addition, 342 were injured or wounded and 294 were taken prisoner. These figures are the best estimates available: such was the lack of organization in the attack that there is no record of exactly how many men were on the "Castillo de Olite".

The war ended only 25 days later, with the victory of Franco's forces despite their failure to take Cartagena on 7th March. The loss of life proved to have been in vain, and the lack of organization in the attack had been so calamitous that little publicity was given to the worst naval catastrophe of the three-year war in terms of the number of lives lost.

The only factor mitigating the blame apportioned to the chaotic Nationalist command of the mission was that the Republican defences had also been very poorly coordinated. By the time the "Castillo de Olite" was hit, it was clear that the mission had failed and that the men on board had no chance of disembarking. The defence of the city had already proved successful before the fateful shell was fired by from "La Parajola", and the sinking was therefore unnecessary by that point.

Most of those who lost their lives were veterans of the conflict, and many were far from home, which for them was Galicia, in the north-west of Spain.

Prisoners of War in Fuente Álamo

The 294 survivors were taken to Fuente Álamo, where they were held captive in the parish church until the end of the war soon afterwards. There are now few locals in the town who can still remember the dishevelled and distraught survivors being housed in the Iglesia de San Agustín, but various individuals recall their return to the town 25 years later, when they were received with warmth, residents remembering their condition when they arrived in March 1939.

The 294 survivors were taken to Fuente Álamo, where they were held captive in the parish church until the end of the war soon afterwards. There are now few locals in the town who can still remember the dishevelled and distraught survivors being housed in the Iglesia de San Agustín, but various individuals recall their return to the town 25 years later, when they were received with warmth, residents remembering their condition when they arrived in March 1939.

Once in power, Franco's administration were understandably unwilling to dwell on what had, after all, been a naval disaster which owed more to the Nationalists' poor planning and organisation than to anything else. But eventually there was to be official recognition of the generous behaviour of the inhabitants of Fuente Álamo: in the official state bulletin of 1966 General Francisco Franco conferred upon the town the titles of "Muy Noble" and "Muy Leal", in thanks for what was termed the "humanitarian efforts" of its inhabitants concerning the prisoners of war from the sinking of the "Castillo de Olite". The main street of the town was named "Gran Vía de los Mártires del Castillo de Olite" in honour of those who lost their lives in the tragedy.

An avoidable tragedy

The sinking of the "Castillo de Olite", then, is widely viewed as a tragedy that could have been avoided.

The first error was, of course, the lack of preparation of the mission. The attackers had practically no information concerning the resistance they were likely to face, and one of the survivors declared that "we were sent to the slaughterhouse". In some ways it can be considered a stroke of luck that the "Castillo de Olite" was the only ship sunk.

The attackers were also counting on support from those who had revolted against the Republicans in the naval uprising in Cartagena. However, they were ill-informed regarding the real situation on the ground: the rebellion had practically been brought under control by the time the attacking fleet arrived.

Furthermore, the ships were sailing into an area fraught with danger. The Republican fleet had had time to sail out of the port towards Algeria before the attacking fleet arrived, but could easily have turned back and attacked from the open sea. In addition there was the risk of attack from the air and by submarine during the journey to Cartagena, which was along coastline held by the Republicans.

The "La Parajola" gun battery

The "La Parajola" gun battery was located 4 km from the centre of the city of Cartagena in the area known as La Algameca Grande, on the headland to the south-west of the port. Indeed the battery can still be seen there, half-way up the slope at an altitude of 164 metres above sea level, with a clear view and line of fire across the entrance to the harbour from west to east. The "Castillo de Olite" was sunk almost at the other side of the entrance, at a distance of 4.8 km from the gun which fired the fatal shell.

The "La Parajola" gun battery was located 4 km from the centre of the city of Cartagena in the area known as La Algameca Grande, on the headland to the south-west of the port. Indeed the battery can still be seen there, half-way up the slope at an altitude of 164 metres above sea level, with a clear view and line of fire across the entrance to the harbour from west to east. The "Castillo de Olite" was sunk almost at the other side of the entrance, at a distance of 4.8 km from the gun which fired the fatal shell.

The hill on which the battery is placed is towards the eastern end of the Baetic mountain range, which runs across the south of the Iberian peninsula and ends at Cabo de Palos, and the strategic emplacement of the gun battery gave it a range of fire which included not only the port of Cartagena but also the island of Escombreras, next to which the Castillo de Olite was sunk. The whole of this part of the Baetic range is characterized by steep slopes and outcrops, an appropriately hostile terrain on which to situate such destructive weaponry.

"La Parajola" was a part of the defensive ring around Cartagena. The guns themselves were built by Vickers, and included 1½-inch and 6-inch artillery, protected by 105cm anti-aircraft guns. The main shells had a range of 35 km and 21 km respectively, while the antiaircraft guns were designed to be effective over a distance of 7 km. Similar artillery was deployed in a series of bases along the coast of Cartagena, from Cabo Tiñoso in the west to Cabo Negrete in the east, providing a strong defensive belt around the port of Cartagena.

The four 6-inch Vickers guns were a 1923 model, and were placed in barbettes with the firing direction being determined by a system consisting of a Vickers directing sight and a Barr-Stround rangefinder. The guns could fire over an angle of 123 degrees, covering the area between Cabo Tiñoso and Cabo del Agua. The angle of elevation was between 10º down and 35º up, with a "dead area" of 2,000 metres. They also covered a land front of approximately 23 km. At the time of the sinking of the "Castillo de Olite" only the number 1 gun was operational. Number 4 had been disarmed, and in the uprising of the previous days the parapets and munitions lifting equipment of numbers 2 and 3 had been put out of action.

As is the case of other gun batteries involved in the defence of Cartagena, the architectural style is curiously "historical", and has modernist touches very much in line with the fanciful designs seen in Spanish architecture of the early 20th century.

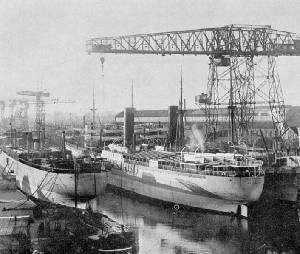

The "Castillo de Olite"

The Castillo de Olite was originally a merchant ship, built in the Droog shipyard in Rotterdam in 1921. It was one of the mass-produced vessels produced in the port at that time, and was practically identical to many others built for the same purpose, i.e. merchant shipping.

The Castillo de Olite was originally a merchant ship, built in the Droog shipyard in Rotterdam in 1921. It was one of the mass-produced vessels produced in the port at that time, and was practically identical to many others built for the same purpose, i.e. merchant shipping.

It first sailed under the name of "Zanndijk", when it was acquired by the "Solleveld Van der Meer & T.H. Van Hattum" shipping company, which deployed it to transport merchandise on the Java-Sumatra routes between 1921 and 1929.

At the end of the 1920s, the Zanndijk was sold to another company, for which it sailed under the name of "Akedemik Paulo" between 1929 and 1932. It was then acquired by the "Nederlandsch Lloyd" company, under whose orders it sailed as the "Zwaterwater" between 1932 and 1936.

In 1936 the vessel was sold to the Soviet Union, whose new economic plan included the purchase of hundreds of merchant shipping vessels from other countries in order to stimulate foreign trade. At this point it was renamed the "Potishev", after a Communist politician from the Ukraine.

In 1938 the ship was captured by Spanish forces. It was still in good enough condition to be used in the Civil War, and in fact would have been far more seaworthy than many other vessels captured and re-commissioned for the war effort. It was at this point that it was renamed "Castillo de Olite", after a castle near Pamplona, and Franco's nationalist forces deployed it in their effort to suffocate enemy sea traffic.